The debate over contraception and abortion has raged around moral issues such as whether or not destruction of a conceptus (a fertilized ovum) is equivalent to destruction of a human life, and whether or not the use of contraception promotes promiscuity in women. I have yet to see the issue of promiscuity in men addressed except as it relates to rape; I have never seen it referenced in any contraception discussion I have read, heard, or watched.

Several issues of major human concern, which I have never seen addressed by those who are anti-choice or against birth control, and which are seldom considered even by pro-choice advocates, include:

- women’s physical well-being,

- human social well-being, and

- environmental well-being (quality of life on this planet).

In the next three blogs, I will address these three issues, which are effectively at the ethical core of the debate over contraception and abortion. These are larger issues about long-term human survival, unlike the false debate about whether a cell (or a cluster of cells) with 46 chromosomes is a human being.

First of all, it’s important to acknowledge up front that the reproductive system, unlike all other bodily systems, is NOT designed for the preservation of the individual. All other systems of the body—for example, gastrointestinal, endocrine, and urinary systems—contribute to the maintenance and well-being of the person in whom they are found.

The function of the reproductive system, by contrast, is procreation and preservation of the species. It does not contribute to homeostasis; indeed, it frequently throws off the metabolic balance of the individual. A pregnant woman may develop gestational diabetes, for example—or osteoporosis, or circulatory problems, or pelvic floor damage, or lower back problems. So whatever else a pregnancy does, it takes a serious toll on the body of the woman carrying it, which can lead to long-term health problems.

Indeed, under circumstances “in the wild,” where no medical care is available, the likelihood of a woman dying in child-birth over her lifetime is about one for every seven to ten women. This dismal maternal death rate persists in many parts of Africa.

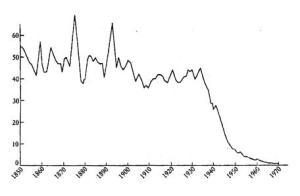

Comparable maternal mortality was also the case in the U.S. in the 1700s and early 1800s. Oddly, in the late 1800s, childbirth death rates actually increased substantially, largely because physicians replaced midwives as childbirth assistants. “Doctors” were often ill trained, were inclined to use instruments, and did not use aseptic technique. So the incidence of puerperal (childbirth) fever rose alarmingly, in some places as high of 40% of all deliveries.

Figure: Annual death rate per 1000 total births from maternal mortality in England and Wales (1850-1970)

J R Soc Med. Nov 2006; 99(11): 559–563.

These figures fit well with information from my own family history. My great-grandfather, an immigrant from Cornwall to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in the late nineteenth century, had a total of twenty one children, with three (sequential) wives, two of whom died in childbirth. And only seven of the children survived to adulthood, one of which was my grandfather.

So it certainly was dangerous to be a woman prior to the mid-twentieth century. And the past high mortality among women may account for much of our culture’s patriarchy; it has always been debilitating and/or limiting to carry, bear, and care for children.

Along with improved medical care, the availability of birth control has enhanced the health and productivity of women in this and all other modern nations. Those who wish to limit women’s access to birth control apparently do not care about women’s health. To try to turn back the clock on the past century’s improvement in the well-being of women is cruel, unthinking, and barbaric.

The next in this series in on contraception and social well-being.

“Those who wish to limit women’s access to birth control apparently do not care about women’s health. ” That’s the key, they don’t seem to care about women as individual human beings and only see them as incubators. It is very disturbing.

It’s like they can’t imagine what it would be like to be a woman and pregnant. Apparently Sheryl Sandberg also didn’t support flex time at work until she, herself, became pregnant and had a child! It’s partly a failure of imagination and empathy.

The more things change the more they stay the same. It is infuriating how a handful of men can alter the fates of so many women and their families. Must every step toward equality but so hard fought and long to win. (sigh) What can we do but what we can do? A well-put and thoughtful article on a very Important subject.

Thanks! I’m afraid we just have to take the long view and continue the pressure. After all, it’s been 150 years since emancipation, and still African Americans are considered by many to be second-class citizens. The existence of an AA in the White House (note the irony) makes about 20% of the U.S. population absolutely apoplectic. As Jesus said, “Love others as you love yourselves.” I believe the haters really don’t like themselves very well. And those who would limit women’s freedom are bound by their own narrow-mindedness.

Jo Anne,

Excellent blog! I had not realized how the childbirth death rate rose after doctors began to replace midwives, but it’s not surprising, for the reasons you cited. The graph you included is certainly dramatic.

In all the brouhaha about birth control, the original idea of Planned Parenthood seems to be overlooked. Both pro- and anti-contraception groups focus on abortion rather than on sensible family planning. By using contraception, a woman is contributing to her own health in various ways–avoiding pregnancy during periods of illness or stress, allowing time to recover after giving birth before becoming pregnant again, postponing pregnancy until she can afford needed medical care, and so on.

She is ensuring health for her family, too. Her husband or partner will suffer less stress and be better able to support her and their children. The children will benefit from a healthy mother who has time for them and is not burdened financially.

A woman who uses contraception proactively is also much less likely to need abortion. Even we who are pro-choice wouldn’t choose abortion as a first choice.

Carol

Thanks, Carol. Contraception certainly IS a women’s health issue – both physical health and psychological health!

Thanks for sharing this well-thought information, Joanne. I was just reading a book about women in the eighteenth century and how so many died in childbirth and how few survived childhood. We don’t often think of that today–but we should.

Kathy, yes indeed, we should. Contraception is basically what liberated Western women from the often deadly burden of constant childbearing. This is truly a women’s health issue. Besides this, contraception has made it possible for married women to have fewer children so that they could contribute creatively to other aspects of society and culture. I believe it was “the pill” that set women free from the tyranny of their gender roles. Back when my mother was young, if you wanted to be a professional woman (including a teacher), you simply didn’t get married.